Financing Canadian Energy Transitions: Challenges and Policy Recommendations

In order to stabilize the pace of climate change, the Government of Canada has pledged to reduce its carbon emissions 30 percent below 2005 levels by 2030 and to eliminate its carbon emissions completely by 2050. Energy transitions and clean technology development are imperative for Canada to effectively and efficiently decarbonize all economic sectors to meet the 2030 and 2050 emission targets.

Clean technology development will lead energy transitions

To achieve Canada’s emission targets, widespread adoption of some already established clean technologies and commercialization of some emerging clean technologies are required. Deloitte Canada and Canadian Institute for Climate Choices (CICC) have identified non-emitting electricity, zero-emitting vehicles, energy efficiency equipment, electric heat pumps and baseboard heaters, hydrofluorocarbon reductions, methane capture, and natural gas fuel switching as established technologies as these are being used in at least one economic sector, they do not face major barriers in scaling up and there is a reasonable expectation that their costs will decline. The same sources marked hydrogen, carbon capture, utilization and storage, direct air capture, small modular reactors, liquid biofuels, renewable natural gas and geothermal as emerging technologies as these technologies are still at early stages of development and face potential barriers to commercialization, mainly due to their high upfront capital requirements and uncertainty regarding their abilities to generate power steadily. For these technologies to become cost-effective, their costs need to go down significantly. Emission modeling by CICC and Deloitte Canada shows that widespread adoption of established technologies is adequate to meet the emission reduction target of 2030, while commercialization of some emerging technologies is required for the deep decarbonization needed to meet the net-zero emission target by 2050.

Market failures in energy transition financing block private sector capital

Retail and institutional investors from home and abroad make up the supply-side of the energy financing market.[1] Transitioning companies, energy transition start-ups, technology developers make up the demand-side of the energy financing market. The energy transition financing market in Canada is faced with two key market failures – hold up problem and information asymmetry.

a. Hold up problem: Projects with large sunk and irreversible initial investments are subject to the hold up problem. Large infrastructure projects with long lives, such as cleantech development and energy transition projects require large upfront investments. Once the investment is made, the cost of providing services from the infrastructure typically is uncertain. This uncertainty over future revenue is one of the key reasons behind the hold up problem.

For instance, after the construction of a hydroelectricity plant, the entities procuring electricity from the plant might be able to negotiate prices lower than the amount required by the builder to recuperate capital costs in absence of a long-term contract. In this case, the project developer, as well as entities who have supplied capital during the construction of the hydroelectricity plant, will face a hold up.[2]

b. Information Asymmetry: Information asymmetry occurs when one party has greater subject-specific knowledge than the other party in an economic transaction. In energy transition financing markets, the project developers (prospective investees) often possess more knowledge on the technologies for which they are seeking investments than the investors. Also, investors often find it challenging to assess the economic viability of the projects due to their unfamiliarity with the technologies and the high cost of assessment. Investors often perceive cleantech as high risk in terms of being disrupted or becoming quickly obsolete.

For instance, the lack of development in the Canadian geothermal sector is due to the investment risk that derives from unavailability of resource information. The power generation capacity of a geothermal reservoir is dictated by its temperature, depth, volume and hydraulic conductivity. The state of these parameters is uncertain and thus estimates of generation capacity are also uncertain. Information regarding the resource can only be obtained by drilling costly exploration and confirmation wells. As investors and project developers might have to spend a significant amount of money to obtain information, geothermal remains one of the most underinvested renewables.

Due to the uncertainty in future revenue and policy, investors financing cleantech projects with high upfront capital requirements have to take on high financing risks which results in high cost of capital for project developers. Project developers often find it challenging to communicate the business case of a cleantech and government financing often fails to signal the investment potential of a project. Additionally, Canadian venture capital firms show reluctance in financing the cleantech projects at an early stage due to the uncertainty regarding revenue.[3]

Policy interventions can mobilize financing

More private sector capital can be unlocked for the energy transition and cleantech development projects if the federal government introduces policies that effectively reduce the financing risks of the projects, provide certainty regarding future return and ensure policy predictability.

Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) which are long-term contracts between the government and private sector entities can be a way forward for financing Canadian energy transitions. PPPs are currently being used by governments to leverage private sector capital and expertise to support the development of infrastructure projects all around the world, including Canada. For instance, the Government of Canada has supplied $3.80 Mn to Lac La Biche County in Alberta to attract private sector investment and expertise for building a Biological Nutrient Removal wastewater treatment facility in the County. PPPs can be applied to both established and emerging clean technologies across all emitting sectors including electricity.

Power Purchase Agreements (PPAs) which are financial contracts between an energy buyer and a cleantech project developer, mostly in the electricity sector, could be leveraged further. Through the contracts, the buyer guarantees the developer a fixed price for energy from a project before a project has been built or after. In return for this fixed price, the buyer locks in an electricity rate for a certain period of time and receives renewable energy certificates (RECs) from the project.[4] PPAs are long-term contracts, lasting 10 to 15 years. If the government could facilitate PPAs between electricity buyers and sellers, it might minimize the hold up problem for investors by providing certainty on future revenue, while reducing the cost of capital for project developers. This facilitation can be done by rewarding buyers for signing long-term contracts.

A Feed-in tariff (FIT) is a subsidy program that can be used to promote investment in cleantech projects. FITs provide project developers a higher price for the clean power (mainly electricity) produced by them, with a view to creating a market for clean technologies that reflects the value of avoided externalities. FITs assure developers an acceptable return upon successful power generation from cleantech. Sometimes, FITs offer an above-market price for clean electricity with guaranteed purchases and advantageous grid access. In a FIT system, the government sets a long-term price for any developer trying to feed its clean electricity into the supply. After receiving grid access, the developer starts to receive the set price for electricity, while incremental costs are passed on to consumers.

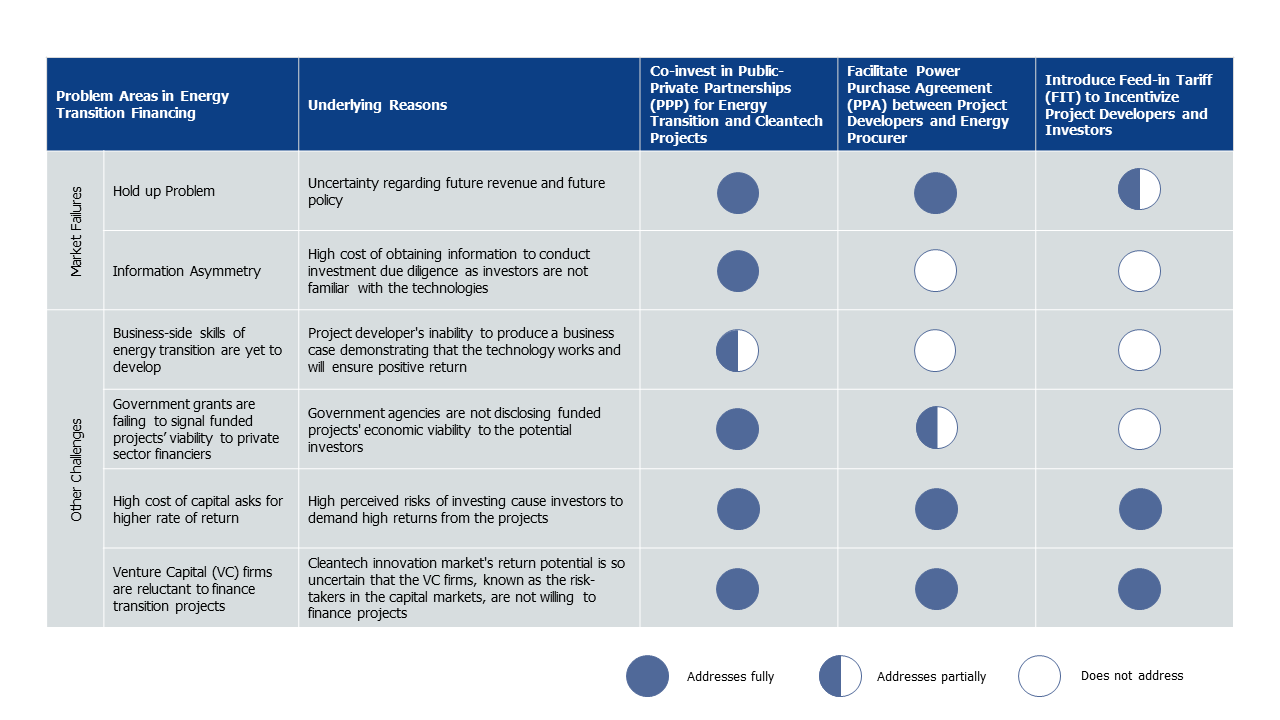

Table 1: Evaluation of Policy Alternatives

An ideal policy intervention would reduce the financing risks of energy transition and cleantech development projects, while also clearly disclosing future return potentials with the private sector investors. The analysis from Table 1 shows that at this moment co-financing through PPPs addresses the majority of the market failures and challenges in every emitting sector, while PPAs de-risk the investment and signal certain future return to the private sector financiers in the electricity sector. A suite of these policies can aid investors with varying risk appetites to explore the Canadian energy transition and cleantech financing market.

[1] Institutional investors mobilize funds to buy securities or other investment assets. Commercial banks, central banks, government entities, venture capital and private equity funds, pension funds, charities, hedge funds are some of the institutional investors. Retail investors buy and sell securities following their personal investment strategy or consulting any online or offline professional trader, but at a smaller scale than the institutional investors.

[2] Hermalin and Katz define hold-up problem as – “When one party makes a sunk, relationship-specific investment and then engages in bargaining with an economic trading partner. That partner may be able to appropriate some of the gains from the sunk investment, thus distorting investment incentives, either toward too little investment or toward investments that are less subject to appropriation.”

[3] Venture capital (VC) is a version of private equity using which investors finance early-stage start-ups and small businesses with commercial viability.

[4] Renewable Energy Credits (RECs) are used to track the ownership of renewable energy production and consumption. These certificates enlist the environmental benefit created by clean energy production. Organizations willing to reduce their carbon footprint often buy RECs.

About the author: Pia Silvia Rozario is an MPP graduate of 2021 with concentrations in Canadian energy and trade policy. She is currently working at the Asia Pacific Foundation of Canada and a Trade Policy and Promotion Consultant. Silvia has more than three years of work experience in management consulting. Energy transitions, climate policy, trade and investment, impact investment, financial inclusion, emerging and frontier markets are some of her many interest areas.

The author can be reached at: https://www.linkedin.com/in/silvia-rozario/